At the core of our theoretical framework is the study of the Amygdala-Prefrontal Pathway. In individuals with Social Anxiety Disorder, the amygdala—often referred to as the brain's "smoke detector"—functions in a state of chronic hyper-reactivity. This subcortical structure, responsible for threat detection and the initiation of the fear response, interprets benign social evaluative cues (such as eye contact, silence, or neutral facial expressions) as existential threats to the individual's standing within the social hierarchy.

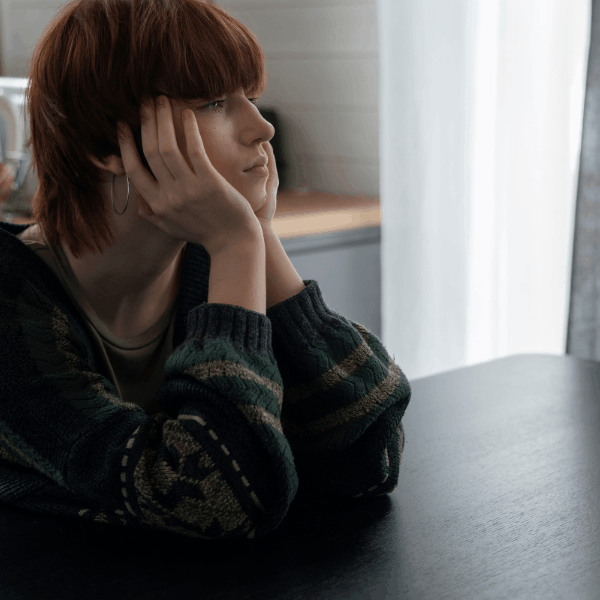

This neurological misinterpretation is not volitional. The individual does not consciously decide to perceive a colleague's silence as social rejection or a neutral facial expression as disapproval. Rather, the amygdala, operating below the threshold of conscious awareness, initiates a sympathetic nervous system cascade that releases cortisol and adrenaline. This cascade produces the debilitating physical symptoms characteristic of social phobia: heart palpitations, tremors, blushing, sweating, and muscle tension.

The Institute's research focuses on the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC) and its failure to provide adequate "top-down" regulation to the limbic system. In neurotypical social functioning, the PFC—particularly the ventromedial and dorsolateral regions—exerts inhibitory control over the amygdala, contextualizing social cues and modulating emotional responses. In Social Anxiety Disorder, this regulatory mechanism is compromised. The PFC lacks the necessary "braking power" to override the amygdala's alarm signal.

Recovery, therefore, is not a matter of willpower or positive thinking. It is a matter of strengthening the neural pathways that connect the PFC to the amygdala, increasing the regulatory capacity of the cortical regions, and systematically retraining the threat detection system to differentiate between genuine danger and benign social evaluation.