Unraveling the Roots of Social Anxiety: A Comprehensive Look at the Causes

Social anxiety disorder affects millions of people worldwide, yet its origins remain one of the most fascinating and complex puzzles in mental health research. Unlike conditions with clear, single causes, social anxiety emerges from an intricate web of biological predispositions, environmental influences, psychological factors, and life experiences that interact in unique ways for each individual.

The question “what causes social anxiety?” doesn’t have a simple answer because the condition rarely stems from one isolated factor. Instead, it typically develops through a perfect storm of vulnerabilities and triggers that converge at critical moments in a person’s life. Understanding these various contributing factors can provide valuable insights for both those experiencing social anxiety and their loved ones seeking to offer support.

This complexity actually offers hope rather than discouragement. When we understand that social anxiety has multiple contributing factors, we also recognize that there are multiple pathways to healing and recovery. Each factor that contributes to the development of social anxiety can potentially become a target for intervention and positive change.

The research into social anxiety causes has evolved significantly over the past decades, moving from simplistic explanations to sophisticated models that acknowledge the multifaceted nature of this condition. This deeper understanding has led to more effective treatments and better outcomes for people struggling with social fear.

The Biological Foundation: Nature’s Role in Social Anxiety

The biological underpinnings of social anxiety demonstrate that this condition has deep roots in our fundamental brain structure and chemistry. These biological factors don’t doom someone to a lifetime of social fear, but they do create vulnerabilities that can be activated under certain circumstances.

Genetic Influences and Family Patterns

Research consistently shows that social anxiety disorder clusters in families, with individuals having a first-degree relative with the condition being two to six times more likely to develop it themselves. This familial pattern suggests a significant genetic component, though teasing apart genetic influences from shared environmental factors remains challenging.

Twin studies provide some of the clearest evidence for genetic contributions, showing that identical twins are more likely to both have social anxiety compared to fraternal twins, even when raised in different environments. However, the genetic influence appears to be complex, involving multiple genes rather than a single “social anxiety gene.”

The heritability of social anxiety is estimated to be around 30-40%, meaning that genetic factors account for roughly one-third of the risk for developing the condition. This leaves substantial room for environmental and experiential factors to influence whether someone with genetic vulnerability actually develops social anxiety.

Interestingly, what appears to be inherited may not be social anxiety specifically, but rather broader traits like general anxiety sensitivity, behavioral inhibition, or emotional reactivity that can predispose someone to various anxiety disorders depending on their life experiences.

Neurobiological Architecture

The brain structures involved in social anxiety form an intricate network that processes social threats and coordinates appropriate responses. The amygdala, often called the brain’s alarm system, plays a central role in detecting and responding to potential social dangers.

In people with social anxiety, neuroimaging studies reveal heightened amygdala activity when viewing faces, particularly those showing disapproval or negative emotions. This hypervigilance to social threat cues can make everyday social interactions feel genuinely dangerous, even when logic suggests otherwise.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for rational thinking and emotional regulation, shows altered patterns of activity in social anxiety. Often, there’s decreased activity in areas responsible for cognitive control and increased activity in regions associated with self-focused attention and negative self-evaluation.

The anterior cingulate cortex, which monitors for conflicts and errors, tends to be overactive in social anxiety, creating a heightened sense of social mistakes and the need for constant self-monitoring during social interactions.

These brain differences aren’t necessarily permanent or unchangeable. Neuroplasticity research shows that successful treatment can lead to normalization of brain activity patterns, suggesting that biological vulnerabilities can be modified through appropriate interventions.

Neurotransmitter Imbalances

The chemical messengers in our brains play crucial roles in regulating mood, anxiety, and social behavior. Several neurotransmitter systems appear to be involved in social anxiety disorder.

Serotonin, perhaps the most studied neurotransmitter in anxiety disorders, helps regulate mood, social behavior, and anxiety levels. Low serotonin activity has been implicated in social anxiety, which explains why medications that increase serotonin availability often prove effective in treatment.

GABA, the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, acts as a natural brake on anxiety and fear responses. Reduced GABA activity can lead to heightened anxiety and difficulty calming down after stressful social encounters.

Dopamine influences motivation, reward processing, and social behavior. Alterations in dopamine functioning may contribute to the reduced motivation to seek social rewards and the tendency to avoid social situations characteristic of social anxiety.

Norepinephrine, involved in the fight-or-flight response, may be overactive in social anxiety, contributing to the intense physical symptoms that accompany social fear.

Environmental Architects: How Life Experiences Shape Social Fear

While biological factors create the foundation for social anxiety vulnerability, environmental experiences often determine whether that vulnerability develops into a full-blown disorder. These environmental influences can occur at any stage of development but are particularly powerful during childhood and adolescence.

Early Childhood Development

The quality of early attachment relationships significantly influences how children learn to navigate social relationships and regulate emotions. Insecure attachment patterns, whether due to inconsistent caregiving, parental anxiety, or other disruptions in the parent-child bond, can create templates for future social relationships marked by fear and uncertainty.

Parenting styles play a crucial role in either fostering social confidence or contributing to social anxiety development. Overprotective parenting, while well-intentioned, can prevent children from developing confidence in their ability to handle social challenges independently.

Highly critical or rejecting parenting styles can create internalized voices of harsh self-judgment that persist into adulthood. Children who grow up with constant criticism may develop the belief that others will inevitably find them lacking or disappointing.

Anxious parenting, where parents model fearful responses to social situations, can teach children that social interactions are inherently dangerous. Children learn not just from direct instruction but from observing how their parents navigate social relationships.

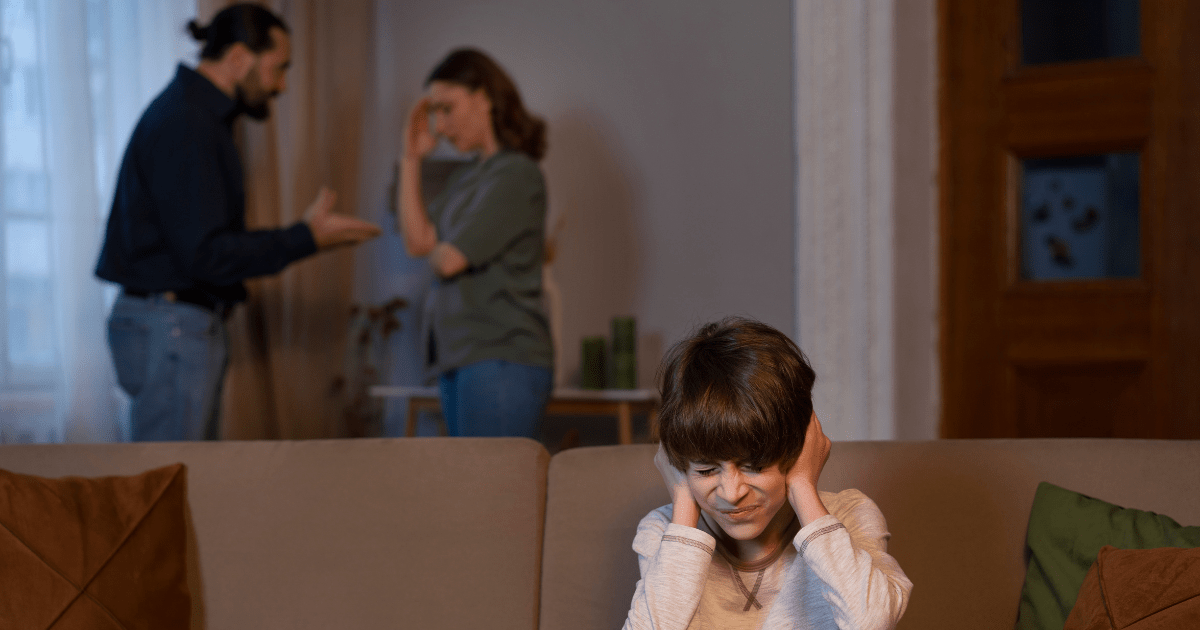

The family’s overall social climate influences social anxiety development. Families that are socially isolated, highly conflict-ridden, or marked by significant stress may not provide adequate opportunities for children to develop healthy social skills and confidence.

Traumatic Social Experiences

Specific traumatic or highly embarrassing social experiences can serve as pivotal moments in the development of social anxiety. These experiences don’t need to be objectively severe; what matters is how they’re perceived and processed by the individual.

Bullying represents one of the most common and potent triggers for social anxiety development. The experience of being systematically targeted, humiliated, or excluded by peers can create lasting associations between social situations and danger.

Public humiliation, whether through academic failure, social rejection, or embarrassing incidents, can create powerful memories that generalize to similar future situations. A single incident of being laughed at during a presentation can create years of public speaking anxiety.

Social rejection experiences, particularly during sensitive developmental periods like adolescence, can profoundly impact self-concept and future social approach behaviors. The pain of romantic rejection, friend group exclusion, or social ostracism can create lasting fears about future social connections.

Even witnessing others experience social trauma can contribute to social anxiety development through observational learning. Seeing peers being bullied or humiliated can create vicarious trauma and fear about similar experiences.

Cultural and Societal Influences

The broader cultural context significantly influences both the development and expression of social anxiety. Cultures that place high value on social performance, conformity, and face-saving may create environments where social anxiety is more likely to develop.

Social media and digital communication have created new dimensions of social comparison and evaluation that didn’t exist for previous generations. The constant exposure to curated, idealized versions of others’ lives can intensify feelings of social inadequacy and fear of judgment.

Academic and professional pressures in competitive societies can extend social anxiety beyond casual interactions to include performance situations that feel high-stakes and personally defining.

Economic factors, including socioeconomic stress and limited opportunities for positive social experiences, can contribute to social anxiety development by creating additional layers of social pressure and uncertainty.

Psychological and Personality Factors: The Individual Contribution

Beyond biological vulnerabilities and environmental influences, individual psychological characteristics and personality traits play crucial roles in determining who develops social anxiety and how it manifests.

Temperamental Foundations

Behavioral inhibition in early childhood represents one of the strongest predictors of later social anxiety disorder. Children who show consistent patterns of withdrawal, wariness, and distress in new or unfamiliar situations have significantly elevated risks for developing social anxiety.

This temperamental style appears early in life, often by the first year, and shows remarkable stability over time. However, it’s important to note that not all behaviorally inhibited children develop social anxiety disorder; supportive environments and positive experiences can help resilient children overcome their initial temperamental vulnerabilities.

High sensitivity, including sensory processing sensitivity and emotional reactivity, can contribute to social anxiety by making social environments feel overwhelming and overstimulating. Highly sensitive individuals may find typical social situations more taxing and stressful than their peers.

Introversion, while not a risk factor in itself, can become problematic when combined with anxiety. Introverted individuals who develop social anxiety may find themselves caught between their natural preference for quieter environments and social demands that feel overwhelming.

Cognitive Patterns and Information Processing

The way individuals process social information plays a crucial role in social anxiety development and maintenance. People who develop social anxiety often show characteristic patterns of attention, interpretation, and memory that bias them toward perceiving social threat.

Attention biases toward threat lead individuals to automatically focus on signs of disapproval, criticism, or rejection while overlooking positive or neutral social cues. This selective attention creates a distorted view of social reality where threats appear more prevalent and intense than they actually are.

Interpretation biases cause ambiguous social situations to be automatically interpreted in negative ways. A neutral facial expression becomes evidence of disapproval; a delayed response to a text message indicates rejection; a moment of silence in conversation suggests boredom or judgment.

Memory biases lead to preferential encoding and recall of negative social experiences while positive or neutral interactions fade from memory. This creates a database of primarily negative social memories that reinforce fears about future social encounters.

Perfectionist thinking patterns contribute to social anxiety by setting unrealistically high standards for social performance. When individuals believe they must be fascinating, articulate, and charming at all times, normal human social imperfections become sources of intense shame and fear.

Self-Concept and Identity Formation

The development of social anxiety often intertwines with the formation of negative self-concepts and identity beliefs that persist over time. These core beliefs about oneself as socially inadequate, boring, or fundamentally flawed become self-fulfilling prophecies that perpetuate social difficulties.

Low self-esteem, particularly in social domains, creates vulnerability to social anxiety by making individuals more sensitive to signs of rejection or criticism. When someone already believes they’re socially inadequate, minor social difficulties confirm rather than challenge this belief.

Social identity concerns, including worries about belonging to valued social groups or maintaining important social roles, can intensify social anxiety. The more important social acceptance feels to someone’s identity, the more threatening social evaluation becomes.

Imposter syndrome, the fear of being exposed as inadequate despite evidence of competence, often overlaps with social anxiety. Individuals may fear that others will discover their perceived inadequacies, leading to intense anxiety in professional and academic social situations.

The Perfect Storm: How Multiple Factors Converge

Understanding social anxiety requires recognizing how various contributing factors interact and reinforce each other over time. The development of social anxiety typically involves a complex interplay of multiple risk factors occurring during vulnerable developmental periods.

Critical Developmental Windows

Certain periods of development appear particularly crucial for social anxiety development. Early childhood attachment formation creates foundational templates for social relationships that influence later social confidence.

The transition to school represents a critical period where children must navigate new social demands and peer relationships. Children who struggle during this transition may develop lasting associations between social performance and personal worth.

Adolescence brings unique vulnerabilities due to brain development patterns, hormonal changes, and intense social pressures. The combination of heightened emotional reactivity and increased importance of peer acceptance creates a perfect storm for social anxiety development.

Young adulthood transitions, including college entry and career beginnings, can trigger social anxiety in individuals who previously managed well in more structured environments.

Maintaining Factors and Vicious Cycles

Once social anxiety develops, various factors help maintain and strengthen it over time. Avoidance behaviors, while providing short-term relief, prevent individuals from gathering evidence that challenges their social fears.

Safety behaviors, subtle strategies used to feel more secure in social situations, can actually maintain anxiety by preventing full engagement with social experiences. These behaviors may include over-preparing for conversations, avoiding eye contact, or relying on others to manage social interactions.

Cognitive biases become self-reinforcing, with negative interpretations of social experiences confirming pre-existing fears and strengthening anxious predictions about future social encounters.

The physical symptoms of anxiety can become triggers themselves, with individuals developing fear of their anxiety symptoms being noticed by others, creating cycles of anxiety about anxiety.

Hope Through Understanding: Implications for Recovery

Recognizing the complex, multifactorial nature of social anxiety causes provides hope rather than discouragement. Each contributing factor represents a potential target for intervention and change.

Biological factors, while significant, don’t represent immutable destiny. Neuroplasticity research demonstrates that brains can change throughout life, and successful treatment can normalize many of the biological abnormalities associated with social anxiety.

Environmental influences, while formative, can be countered through new, positive social experiences and relationships. Therapeutic relationships provide opportunities to experience accepting, non-judgmental social connections that can help heal old wounds.

Psychological factors, including cognitive patterns and self-concepts, are particularly amenable to change through appropriate interventions. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and other evidence-based treatments specifically target these maintaining factors.

Understanding the causes of social anxiety can reduce self-blame and shame while increasing motivation for seeking help. When individuals recognize that their social anxiety results from understandable factors rather than personal weakness, they’re more likely to pursue effective treatment.

The multifactorial nature of social anxiety also explains why treatment approaches need to be comprehensive, addressing biological, psychological, and social factors simultaneously. The most effective treatments recognize and target multiple contributing factors rather than focusing on single causes.

Most importantly, understanding causes provides hope that change is possible. Social anxiety may have complex roots, but with appropriate support, evidence-based treatment, and personal commitment, these roots can be untangled and healthier patterns can take their place.